Authors: Manana Kveliashvili; Aydan Yusubova

“If you look at the geographical distribution of the Laz people you will see that they are always inhabiting in mountainous areas, close to the sea. We have no land suitable and sufficient for agriculture. Therefore, the sea for the Laz people is Kve-kana (Georgian: “Kvekana” means the country; “Kana” means harvest-field). I. e. the sea is both the harvest-field as well as the country. If the others are harvesting sustenance in the land, then God conferred to the Laz the sea. The Laz goes out to the sea and fishes,” – with these words, Mirian Numanishvili starts talking about the Laz people.

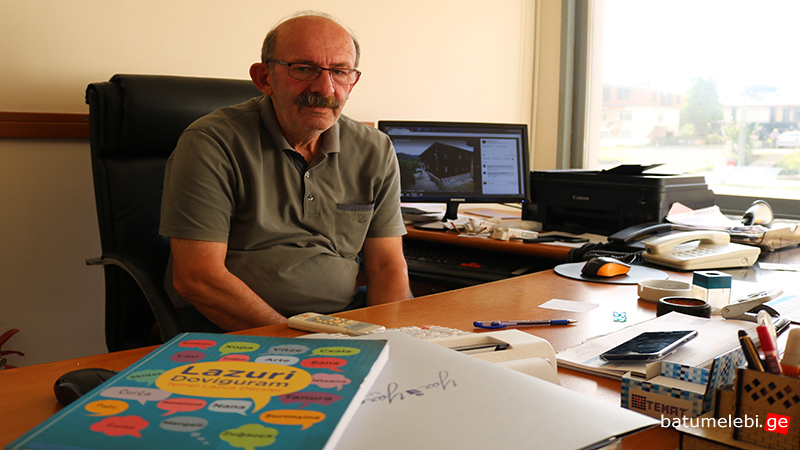

Mirian is the Laz. The famous boatwright of Georgia’s Black Sea Coast, and, perhaps, even the last boatwright too – that knowledge about the production of wooden boats, which Mirian has, no one else has in Georgia.

“The boat is not made as an apple box is made. It has its own secrets, how to hammer boards on each other, how to join beams… I was still a child when I watched how the boat was built. My grandfather was a fisherman, my father too. They were always in the sea. They have been fishing and lived by it. My father was always dreaming – if only you were born earlier and started making boats earlier, we would fish together. I studied in Tbilisi in the 70-80s. At that time a famous boatwright, Ali Khorava lived in Sarpi, when I was arriving at the weekends, I was standing and watching. Then I started too. First I made my first boat, then the second, the third and here I am … “,– says Mirian.

Mirian wanted to pass on his knowledge to the new generation, but “They are not very interested. Imagine, I’m building a boat, and a student stares at the phone. This is not the way this craftsmanship is taught“.

According to Mirian, the fishing tradition has disappeared in Sarpi. Laz no longer go out into the sea and catch fish. His house is located on the seaside, the central highway separates the house from the sea, however, for more than five years now he has not gone to sea by boat.

“Laz children are growing up in Sarpi, although they know that Laz people have been connected to the sea since time immemorial, but the interest disappears. There are no conditions to go to sea on a boat and catch fish or just take a walk on a boat. None of the harbors is located on the Black Sea coast, from Sarpi to Batumi. The government should build small harbors – if there will be no fish in the sea, the boat might be used for tourist boat trips, it will be very good. Traditions will not be lost, and the younger generation will be interested in this, as it will bring them income,” – says Mirian.

80-year-old Seyhan Ozkan is the oldest boatbuilder on the Black Sea coast of Turkey. In Hopa, the city of Turkey, whomever you’d ask about the Master Seyhan, each will show his whereabouts in the harbor.

The Master Seyhan is Laz. For 45 years now he has been making boats. At first, he was a craftsman of furniture. At the age of 35, he quit making furniture and started building boats. Everyone says that he is the best in his business. For many years, he independently has built ten boats only with his own hands. The technological progress has brought – the last two decades, with his own hands he makes only those parts that are connected with wood. The rest is the work of special equipment and knowledge of their use. The Master Seyhan is the last boatbuilder in Hopa.

“No one else is preparing boats, except me in Hopa. We used to be many, but no longer, they’ve passed away. Modern boats are now common, nobody uses wooden boats, so young people are no longer interested in building them,” – says Seyhan Ozkan.

The Master Seyhan said she wanted to pass his knowledge to the new generation but it did not worked out.

“I had five or six apprentices, but they were not very much interested in this business. Since this is not a profitable business, there is no demand for this specialty. Previously, the construction of boats could sustain a family, now it has become more like a hobby. If this continues, the culture will disappear,” – says Ozkan.

Mirian and Seyhan are both Laz, both of them are boatwrights, both speak Laz language. If Mirian will need to write a Laz word, for this he uses the Georgian alphabet, Seyhan – the Latin one. Laz language is Kartvelian language, which today, according to various sources, is spoken by more than 1.6 million people. Of these, about 2,000 Laz people live on the territory of Georgia. The main area of their resettlement is in Ajara, on the territory of Sarpi-Kvariati. As for Turkey, Laz people live in the provinces of Artvin, Rize and Trabzon. The historic Lazeti (also: Lazona, Lazistan) is now part of the Republic of Turkey. The Laz language was added to the endangered language group by UNESCO.

Turkey, Arhavi. Summer houses of the Laz fishermen from Arhavi Photo: Manana Kveliashvili / Batumelebi

The Laz people living in both countries have a common problem – the Laz language disappears. The Laz youngsters can/are no longer speaking the Laz language.

“Our young people understand the language of Laz, but they cannot speak it – they do not often deal with the language of Laz. The Laz language is no longer topical as it was before. Now five percent speaks the Laz language. Nobody speaks in Laz language at homes. Therefore, the Laz culture is almost lost. Language is the exactly what makes the culture alive. I do not think that we have any special culture left. The only thing left is that at the weddings they are singing in Laz language and that’s it. But not everyone already does that,” – says Seyhan Ozkan.

In Turkey, in the town of Arhavi, built on the Black Sea coast, most of the population is Laz. In a densely populated town the Laz culture is preserved. When entering any institution you will definitely see some object, which is related to the Laz people. This can be a portrait of a Laz woman, made on a wood, who collects tea, the mock-up of the old Laz house or some musical instrument of Laz people. The bus station building in the center of Arhavi has the shape of the Laz house. The Laz architecture details can be found in the local cafes and on the walls of houses. The Laz have a status of ethnic minority in Turkey.

Bus station building in Arhavi, built in accordance with Laz architecture Photo by: Manana Kveliashvili / Batumelebi

The fisherman from Arhavi and his wife at the summer house of fishermen Arhavi, Turkey. Photo by: Manana Kveliashvili / Batumelebi

The Laz people, residing in Turkey, have access to various literature, written in the language of Laz. Among them, they can read the fairy tales of the Pinocchio and Puss in Boots in Laz language.

Osman Shafak Buikli is Laz. He lives in Arhavi. We came to him to talk about the Laz language. He has written three books in Laz language. He says that his children understand the Laz language, but can not speak in it. Like most of the younger generation.

“The Laz language was recently added as an elective subject from the fourth grade to the eighth grade. It exists, but it is not paid due attention. Some children choose this subject, some – not. Parents are not interested in their children learning the Laz language. How they will use it in the future? – that’s the way they think. Because of this, they do not teach children their native language, they prefer English,” – says Osman Shafak Buikli.

According to Osman, there are small linguistic differences between the Laz people living in Georgia and Turkey, but they understand each other. When two Laz meet each other, wherever they live, they can still talk the Laz language – he says.

As for Georgia, according to Laz, living in Sarpi, due to the fact that they do not want the state or any group to accuse them of separatism, they have not expressed an initiative of teaching the Laz language in schools, and they do not plan this for the future either. The Laz believe that the best way to preserve the language is to speak in it in the families.

Even though in scientific circles of different countries there are different opinions regarding the Laz people, Georgian scientists consider the Laz people as one of the branches of Georgians. Chanet-Lazeti is historically known as part of the Georgian state.

Since ancient times, Chaneti belonged to the Kingdom of Colchis. In the next period, at the beginning of our chronology, for the first century, the territory in the east of Trabzon was part of Colchis, including the part of Rize, also the west of the Chorokhi Valley. Over the centuries this area was a constant battlefield. The territory of the historical Lazeti sometimes was the part of Georgia and sometimes not. The present boundaries were established in 1921.

The Treaty of Kars signed between Soviet Russia and Turkey on March 16, 1921, and the Transcaucasian republics of the Soviet Union and Turkey on October 14 of the same year, has recognized the village of Sarpi as the last point of the southern borders of Georgia. Until 1926 there was no exact demarcation of the border. The border was drawn in the middle of the village of Sarpi by the Boundary Commission in 1926. One part of Sarpi turned out to be part of the Republic of Turkey, and the second part – remained in the composition Georgia.

If you ask about the identity of Laz, who lives in Georgia, he will definitely say that he is Georgian. And if you’ll ask the same question to the Laz living in the Republic of Turkey, he will tell you that he is Laz and his native language is the Laz language.

The demarcation of the border divided the village of Sarpi and the people of Laz living in it into two parts. The relatives were separated from each other, because Soviet Georgia had a closed border with Turkey. On the Georgian side of the village Sarpi still remember that, when someone was dying on our side, on the day of funeral, the villagers, who remained on the Turkish side, were gathering on a hill on that other side to honor the memory of the deceased.

Nodar Kakabadze is the Laz. Up to 14 years his name was Raphet Kaba Oghli. His family, as well as the majority of Sarpi population, had a Turkish surname.

“When the Ottomans entered Ajaria, they decided to conduct a census of the population. They were hindered by the fact that the Laz people had Georgian surnames. So they changed the surnames to everyone. To tell you by the example of my ancestors: they were three brothers – Memed, Osman and Ali. Their descendants had surnames – Kaba Memed Oghli, or in other words, the children of thick Memed, Kaba Osman Oghli, or in other words, the children of thick Osman and Khira Ali, or in other words, thin Ali.

Lavrentiy Beria issued a decree in 1947 that prohibited Turkish names and surnames. Residents of Sarpi had to once again change their names and surnames. This time we had a choice – everyone took the name and surname they wanted to.

We, Kaba Memed Oghlis became Kakabadze. Khira Oghli became Khorava, Kaba Osman were left on the Turkish side and till present they are Kaba Osmans.

I clearly remember, I was in seventh grade when the decree was issued on changing the name and surname. My math teacher Camelia Mgeladze gave me the name. She approached each child – you will be this, that will be your name. When she came to me, she gave me the name Nodari. Thus, I Raphet Kaba Oghli became Nodar Kakabadze,” – recalls Nodar Kakabadze.

All rocks invading the sea had their names. When the fisherman caught a fish and returned home from the sea, on the way they asked where he was fishing.

And he was answering, telling the name of the rock, near which he has caught the fish. “The Kvaospao – was a big stone, it has been destroyed by the sea. 5 men could stand on the stone and fish with Chino (Chino – a long stick used for fishing). There were also a Kvachaghana, a stone of Seidoghli, a Kvachkvadei, Sumjuma. Today only part of a Kvaomkhaze is left, “- says Mirian Numanishvili. Kvaomkhaze is the only one left on the beach of Sarpi today – stepped rock invading the sea. In summer, tourists and locals gather on this rock.

“It had a total of 11 steps. We, the Laz people, as soon as we stepped on it, we were learning to swimming. When we were standing on the first step of the Kvaomkhaze, we were kicked from behind, thrown into the sea, and that’s all, we were already baptized. The eleventh step was the highest and hardest point for jumpThe one who jumped from this point with his head and made a flip, he was already a professional. Kvaomkhaze no longer has that part where the eleventh step was. The coastline was strengthened and during those works it was destroyed,” – says Mirian Numanishvili.